Full source code for the latest iteration of this project is here, and here and here.

The Problem: Playlist Rot

I maintain a pretty large Tidal playlist. Over time, a few songs on any streaming service become unavailable as licensing changes. Often, when a streaming service retires a song, they replace it with a different version of the same song, like a remaster. And sometimes the service has multiple versions of the same song, like the original album release and another copy on a “Best of” compilation. When they retire one version, they still have the other.

Anyways, since I have a large playlist, every week or two another few songs become unplayable, while suitable replacements sit there in the streaming service’s library, just waiting to be found and enjoyed.

The Solution: Kubernetes + Flyte (Obviously)

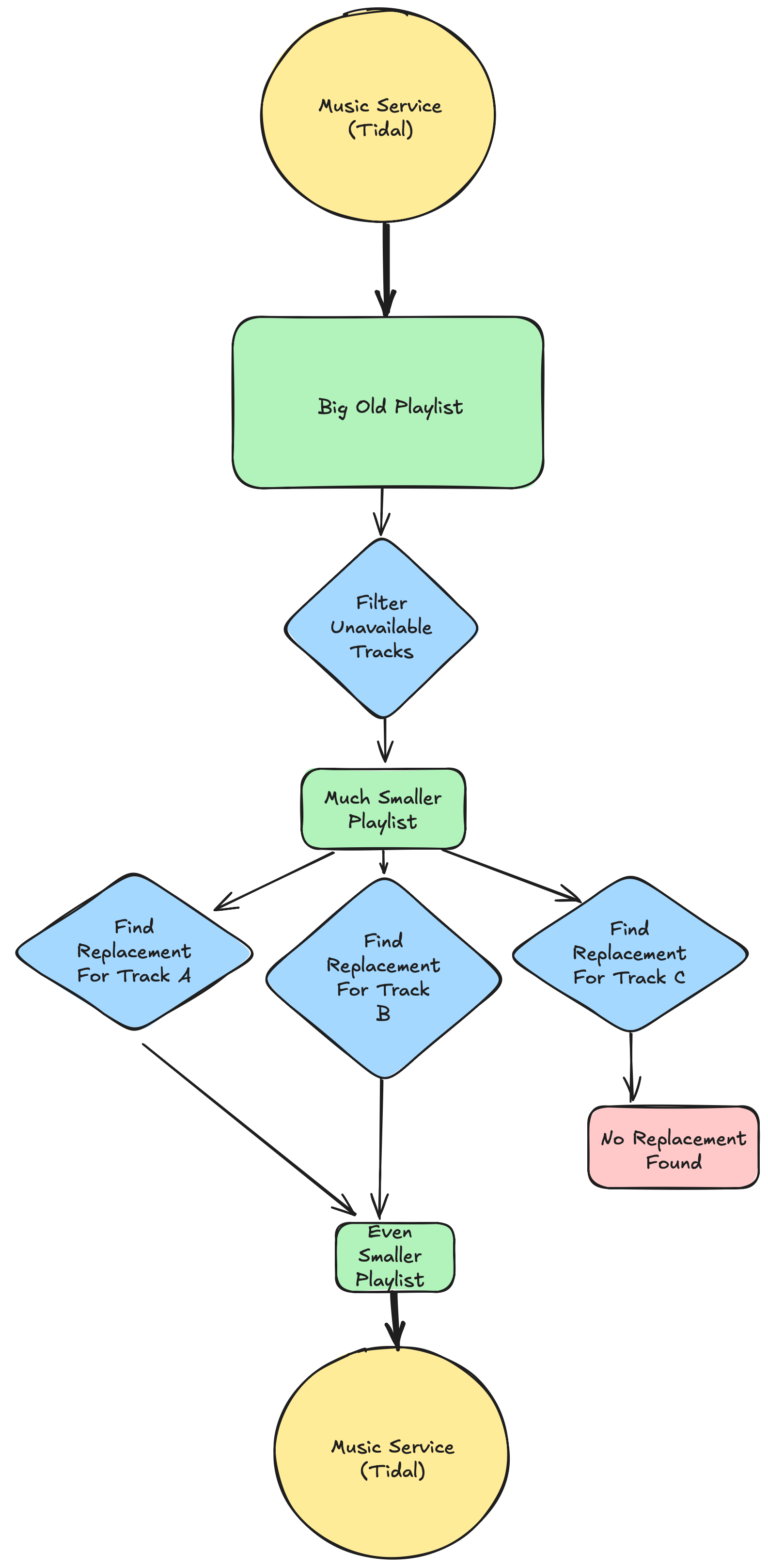

The simplest solution to this problem is obviously to leverage my existing home Kubernetes infrastructure to host a Flyte instance orchestrating a custom, horizontally scalable workflow that scans my playlist for unavailable tracks, finds suitable replacements for the missing tracks - where possible - and publishes a new playlist comprised of replacement tracks.

👉 The simplest solution is usually the best one.

👉 Speaking of simplicity, I left Kubernetes out of the diagram, but it’s there, you’ll see it later.

Semi-automation

Why create a new, small-ish playlist of replacements instead of just updating the larger playlist with the replacements?

For one thing, the unavailable songs have silently (in more ways than one) vanished from my life in a most unauthorized and unannounced fashion. It’s great to hear them once again! I didn’t even know I was missing them, and having them in a dedicated playlist of disappeared songs is nice.

Second, putting them in their own playlist allows me to review them for correctness, not just nostalgia. I can detect false positives, delete them, and improve my matching algorithm. If I add them to the giant playlist, errors won’t stand out very easily.

I can merge the corrections into the main playlist at my leisure.

👉 Not every workflow benefits from full, end-to-end automation.

👉 Don’t automate away the fun!

What is a playlist, anyways?

Here’s a Tidal playlist, in JSON format, simplified by my code to include some human-readable information and the all-important Track Identifier.

It’s a list of individual Tracks.

[

{

"name": "I'm Bored",

"artist": "Iggy Pop",

"album": "New Values",

"version": null,

"num": 4,

"id": 661485,

"artists": [

"Iggy Pop"

],

"available": true

},

{

"name": "Fight The Power: Remix 2020",

"artist": "Public Enemy",

"album": "Fight The Power: Remix 2020",

"version": null,

"num": 1,

"id": 152663861,

"artists": [

"Public Enemy",

"Nas",

"Rapsody",

"Black Thought",

"Jahi",

"YG",

"Questlove"

],

"available": true

}

]

What is a Track, anyways?

A Track is a song. A Track, on any music streaming service, has an ID. The ID can be an integer or a string, but it’s the only thing you need to play some music on a playback device. As far as your playback devices are concerned, a Playlist is a list of Track IDs and nothing else.

The other fields are useful when you want to find two tracks that are “the same”, like when transferring a playlist from one service to a competitor’s service, where the IDs will be completely different for each track.

They’re also useful when you want to find substitutes for a song that is no longer available. Two Tracks with different IDs but identical or similar values for the other attributes might be the same song.

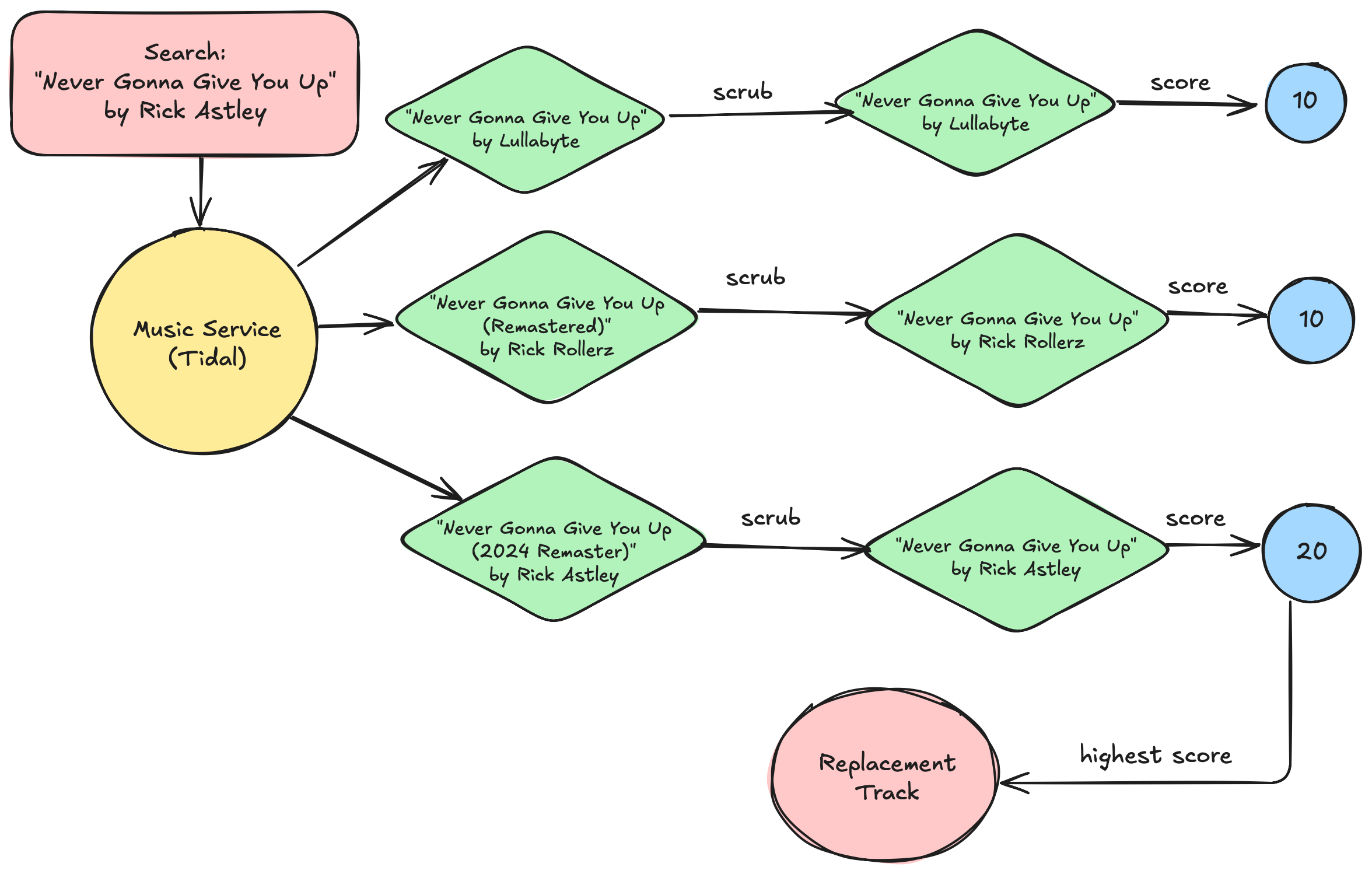

Track names are messy

Here are some track names from my playlist.

- Red Right Hand (2011 Remastered Version)

- Tour De France (2009 Remaster)

- Prisencolinensinainciusol (Remastered)

- Paranoimia (feat. Max Headroom) [7" Mix] [2017 Remaster]

That’s four vastly different parenthetical variants of “Remastered”. When looking for sameness between tracks, we can improve the likelihood of a match (as far as human ears are concerned) by “scrubbing” out the variants of “Remastered”.

And that’s just the name field, the album field is just as unstandardized. And different streaming services have different formats for “Remastered”, “Rerelease”, and other attribute modifiers.

Comparing Tracks

How do you know if two tracks are “the same”?

Start simple and refine as needed.

First, scrub both tracks to make valid matches easier to find.

def scrub(ot: model.Track) -> model.Track:

"""Remove attribute string fragments that inhibit matching, e.g. '(Remastered)'."""

return model.Track(

id=ot.id,

name=ot.name,

artist=ot.artist,

album=ot.album.replace(" (Remastered)", ""),

artists=[],

available=ot.available,

)

The artists field is not very useful. Artists sometimes get creative with the characters in their names, or change their names over time. It’s easier to just zero out the field than try to sort it and reconcile machine-confusing differences.1

We can also do some light scrubbing of the album name to make matches more likely.

Next, we can compute a score representing the relative sameness of two tracks. If the names of two tracks differ, they aren’t the same track. The more other fields match up, the more likely it is that the tracks are the same. Simple!

def score(candidate: model.Track, target: model.Track) -> int:

"""Return a match score representing alikeness of two Tracks. Higher score = more alike."""

if candidate.name != target.name:

return 0

s = 10

if candidate.artist == target.artist:

s += 10

if candidate.album == target.album:

s += 10

return s

After reviewing the output we can determine the value of complexifying the scrubber or the scorer. Maybe we keep getting lucky and the tracks that Tidal makes unavailable don’t need much scrubbing to find a replacement.

Basic Algorithm

The basic algorithm, then, is pretty simple:

- Fetch the playlist

- Iterate each Track (song)

- If the Track is

available, continue iterating - Otherwise, use the music service’s Search API to find Tracks that could be replacements

scrubtheunavailbletrack, modifying fields to make it easier to match- Iterate the replacement candidates,

scrubbing each one - Pass each candidate to the

scorefunction - Sort the candidates by score

- The candidate with the highest nonzero score is our replacement!

Later, we can manually (aurally! 👂) review the selected replacements and, if needed, refine the scrubber/scorer to produce better outcomes.

What about multiple replacement candidates with the same score?

Moving right along!

👉 If needed, we can review the output and refine the scoring to reduce duplicate scores. Doing so prematurely is a waste of time.

Is that Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

Yes. Please email if you’d like to invest.

Prototype

I already had working code to download a Tidal playlist and iterate/manipulate the Tracks. That provided a platform for rapidly iterating to a simple prototype that did everything I needed. But it had several glaring flaws.

- It didn’t run on Kubernetes. It ran on my laptop. But what if I closed my laptop? Then it wouldn’t run at all. Big problem!

- It wasn’t scalable. The prototype remedied

unavailabletracks serially - one after the other. My first run unearthed about 50 such tracks. If it takes 1 second per track, that’s almost a whole minute! I’m way too busy for that. Tracks should be remedied concurrently. Sure, I could use Python’s concurrency libraries, but what if I close my laptop? - Obtrusive caching. Between logical stages I either wrote a file “manually” with Unix pipes, or with Python code.

- Mish-mash of tooling. The full prototype was two Python programs, two JSON files, the

jqutility, andmake. What a mess! What if I could use just one powerful tool?

Clearly I needed a parallelizable Kubernetes-native workflow orchestrator. That’s Flyte!

Here’s the prototype. In “The Mythical Man Month”, Fred Brooks says, “Plan to throw one away; you will, anyhow.” Let me know after you’ve read this and I’ll throw it away. I don’t need it anymore!

Flyte

Installation

The Flyte quick start is amazing, I had things up and running very quickly, with one hitch: although I do have my own Docker registry, the Flyte sandbox (a Docker container running the k3s Kubernetes distro) needed to be configured to tolerate the insecurity of my local Docker registry.

That’s simple enough, I just needed to update a k3s config file like so:

mirrors:

"registry.localdomain:32000":

endpoint:

- "http://registry.localdomain:32000"

This file needs to go into /etc/rancher – inside the Docker container that’s running a tiny k8s cluster for Flyte development. It turns out this is a bind mount, meaning it’s a directory on my laptop mapped into the Docker container. If I can locate the laptop directory, I can add/modify the file and the k3s distro will find it inside the container.

% docker inspect --format='' flyte-sandbox | jq '.[] | select(.Destination == "/etc/rancher")'

{

"Type": "bind",

"Source": "/Users/mp/.flyte",

"Destination": "/etc/rancher",

"Mode": "",

"RW": true,

"Propagation": "rprivate"

}

Creating /Users/mp/.flyte/k3s/registries.yaml and restarting the flyte-sandbox Docker container got the sandbox reading from my home Docker registry.

After that, I was able to execute the Quickstart Guide’s hello world workflow.

Paradigm Shift

Flyte encourages a functional programming style and discourages side effects. My prototype was written in an imperative style and was full of side effects.

While my prototype worked and demonstrated what needed to be done, it wasn’t as simple as dropping it into a Flyte workflow - it would need some refactoring to get into a functional style.

I conceded that the final task in the workflow would have to have side effects: creating a new playlist. The rest could be pure functional.

Before jumping into the refactor, I stubbed out some of the tasks so I could learn more about Flyte and validate my setup.

For example, here is a fetch_playlist() task, stubbed to return tracks without the costly API call to the music service:

import flytekit as fl # type: ignore[import-untyped]

from core import model

from orchestration import image_spec

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List

class Track(BaseModel):

available: bool

id: int

name: str

@fl.task(container_image=image_spec.DEFAULT, cache=True, cache_version="v2")

def fetch_playlist(playlist_id: str, path_to_creds: str) -> List[model.Track]:

print(f"🔑 Reading credentials from {path_to_creds}")

print(f"🥡 Fetching Tidal Playlist {playlist_id}")

return [

model.Track(id=1, name="foo", available=True),

model.Track(id=2, name="bar", available=False),

model.Track(id=3, name="baz", available=True),

model.Track(id=3, name="thip", available=False),

]

That’s good enough to flesh out a full workflow to see how the parts will fit together.

Along with a few other simplified tasks I could run the fledgling workflow against my local Flyte sandbox, learn its caching model, how its Promises work, and even take a quick detour through functools.partial so I could map a fanout over my unavailable Tracks.

partial_task = functools.partial(tasks.find_new_track, path_to_creds=path_to_creds)

new_tracks = fl.map_task(partial_task)(old_track=unavailable)

Initially I used a @dynamic but as I got to better understand the implications and hit some difficulties, I thought it might be easier to use map_task. It was!

My first working workflow looked like this:

import flytekit as fl # type: ignore[import-untyped]

import tasks

from core import model

from typing import List

import functools

@fl.workflow

def remedy_tidal_wf(playlist_id: str, path_to_creds: str) -> List[model.Track]:

playlist = tasks.fetch_playlist(playlist_id, path_to_creds)

unavailable = tasks.filter_unavailable(playlist)

partial_task = functools.partial(tasks.find_new_track, path_to_creds=path_to_creds)

new_tracks = fl.map_task(partial_task)(old_track=unavailable)

remedied = tasks.filter_nones(new_tracks)

return remedied

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

print(remedy_tidal_wf(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2]))

It worked from the local sandbox, the remote sandbox, and as a Python executable, making it easy to debug. I had to write and call tasks.filter_nones() instead of a simple list comprehension because remedy_tidal_wf is a Flyte DSL that looks like Python, but is not actually Python. new_tracks is a Promise that will be lazily materialized when passed as input to another task. Inside remedy_tidal_wf, it’s not a list that can be iterated. That was a key bit of info!

Next Up

In Part 1 I will deal with Secrets and local development infrastructure. In this workflow I need to authenticate to a music service. How can I do that in a way that works in the local sandbox, the remote sandbox, the plain Python main(), and eventually in my own Kubernetes cluster? How can I manage the various commands and tools I need to run as I ramp up my understanding of them?

Stay tuned!

-

Are

SimonandGarfunkeltwo unique elements in anartistslist, or is it a single element,Simon & Garfunkel? It depends! ↩